When Japanese pianist Chieko Hara passed away in 2001, the attentive people in charge of sorting out her possessions found something interesting among her papers. She was a musician, so of course, they did find quite a bit of music. But the rather amazing thing that they discovered among her papers was an unknown composition by German composer Johann Sebastian Bach who had died some 250 years previously. As fortunate as it was remarkable, it was an unknown composition, a Wedding Cantata that has since been assigned the number 216 in the Bach Werke Verzeichnis, that catalog of all Bach’s works that scholars and musicians use to identify each specific work by the master.

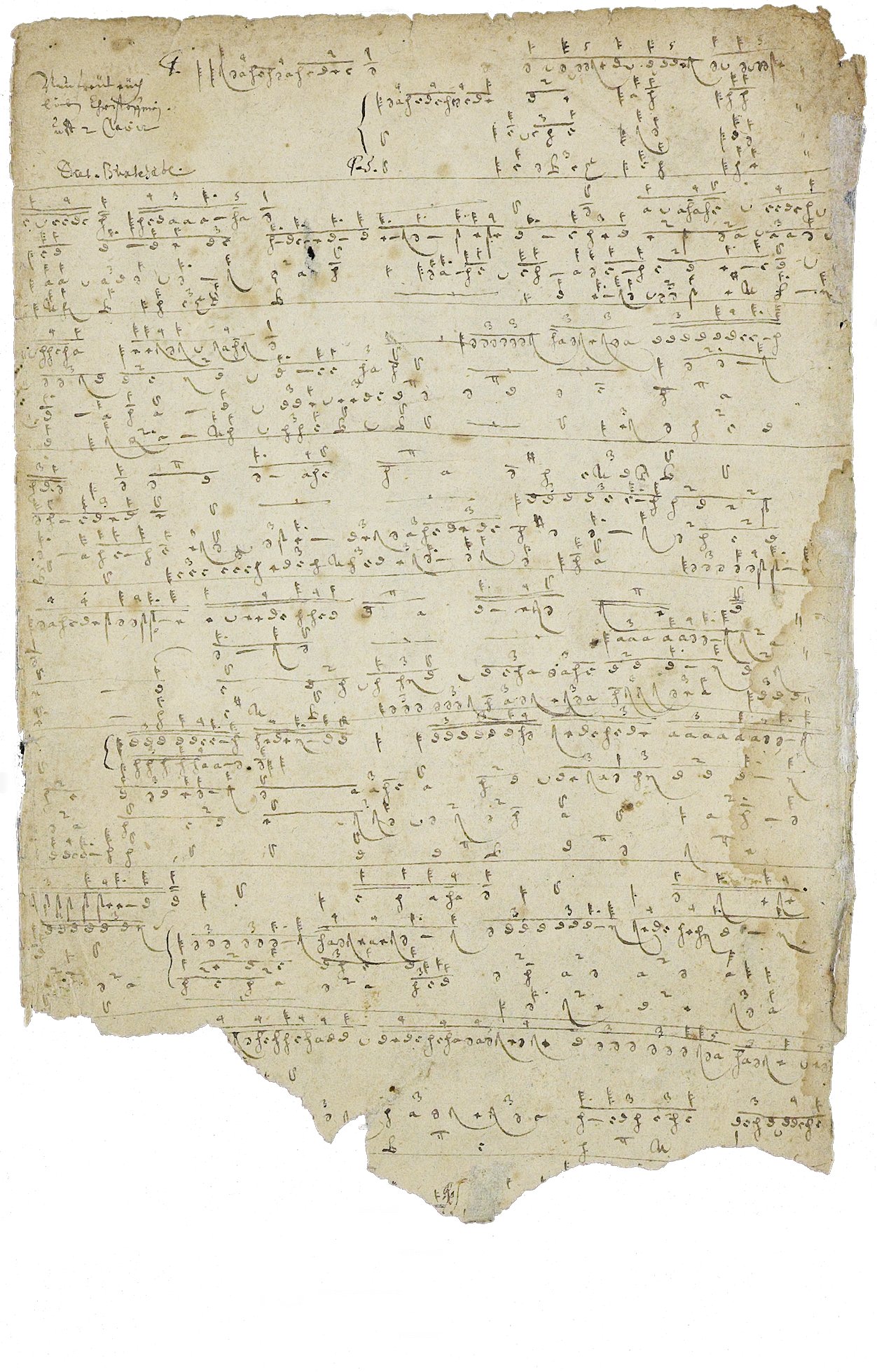

Perhaps even more remarkable than Madame Hara’s Bach mystery cantata is the 2005 discovery of the oldest known manuscript in Johann Sebastian  Bach’s handwriting: organ music he had transcribed at the age of 15 in that rather arcane German organ tablature that was still in use when young Bach was learning the art of pipe organ performance and composition. How did such an early schoolbook example survive time’s heartless passage when so many of his mature works succumbed?

Bach’s handwriting: organ music he had transcribed at the age of 15 in that rather arcane German organ tablature that was still in use when young Bach was learning the art of pipe organ performance and composition. How did such an early schoolbook example survive time’s heartless passage when so many of his mature works succumbed?

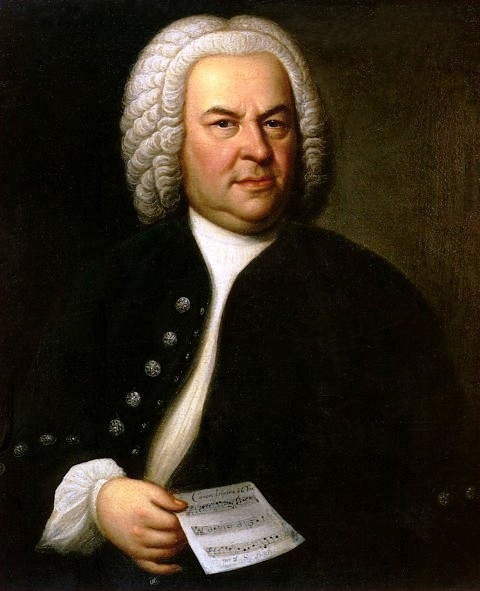

And there are even more incredible examples of this sort of happenstance: Music professor Paul Brumenroeder in Strasbourg had the great good fortune of owning one of the 19 known published examples of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. He would play the Goldberg Variations from this very example, marked with ancient “corrections” presumably entered by the only one who could “correct” the music, Johann Sebastian Bach himself. One day in 1974, musicologist Alan Main of the French Ministry of Culture was visiting, and professor Brumendroeder showed him this treasure. What Mr. Main noticed, was not only the “corrections” but a number (fourteen, precisely) of carefully written yet cryptic musical “compositions” in the back of the pamphlet. There was something familiar about one of those cryptic pieces of music in the back of the book. As it was discovered, one of them was the same music that appeared in Elias Gottlob Haussmann’s 1747 painting of the master. In the painting,  Bach is holding a sheet of music so we the viewer can see it, but in a way that would make it upside down for Bach himself. Unless, of course, this piece of music was something to be performed both right-side up and upside down! It turned out to be a 6 voice canon which was designed to be performed both right-side up and upside down (in inversion) simultaneously by no fewer than six instruments.

Bach is holding a sheet of music so we the viewer can see it, but in a way that would make it upside down for Bach himself. Unless, of course, this piece of music was something to be performed both right-side up and upside down! It turned out to be a 6 voice canon which was designed to be performed both right-side up and upside down (in inversion) simultaneously by no fewer than six instruments.

This copy, along with Bach’s 14 cannons on the Goldberg Variation theme now resides in the French National Archives which acquired the pamphlet shortly after Mr. Main’s discovery.

And there have been many surprising discoveries apart from actual musical manuscripts that surface from time to time. In 1991 Hungarian composer Zoltán Göncz pointed out that the great “unfinished” Contrapunctus XIV of Bach’s epic Die Kunst der Fuge was, in fact, a permutation fugue that was designed to serve as the final piece of the work.

But so far we have been discussing works of Johann Sebastian Bach that we didn’t know existed that have mysteriously appeared, when the nominal subject of this little essay addresses the works that we know to have existed that have then mysteriously vanished. It is, on that matter, we now turn our attention.

Bach’s method of thinking was such that he composed in “sets” of works. For instance, the aforementioned Die Kunst der Fuge subjects a simple melodic fragment into service as the DNA for the entire series of fugues. The two volumes of Das Wohltempemperierte Klavier are each a set of preludes and fugues starting from C Major proceeding up by alternating major/minor mode a semitone at a time to all possible keys. If a particular prelude or fugue were not present in the volume—say there were no G Major prelude—we would assume that it was missing, and not that Bach just didn’t “feel” G Major during the composition of the work.

From 1717 to 1723, Bach served as the court composer/musician to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Kothen. The young prince had a real thing for music. Where Old King Cole had fiddler’s three, the bachelor prince maintained an orchestra of 18 musicians. This was quite an expense for such a small principality, but if you are a young prince, you can pretty much do what you want. Bach was as prolific a composer as he was a thorough one. It was a Calvinist court and which for the Lutheran Bach meant he did not compose for the church where music was not allowed, but for the court itself.

And that court had a well-equipped 18-member chamber orchestra whose sole purpose was the enjoyment and appreciation of the prince and his guests. Aside from concerti and other compositions that utilized the prince’s orchestra, Bach composed six each partitas/sonatas for violin and cello. Time has revealed the existence of three such for viola da gamba, but with six for violin and cello, why would there not be six for viola da gamba? The keyboard partitas some think were composed here at Kothen, but others think they were composed at his subsequent and final layover in Leipzig. In any case, we are now discussing the Seven Keyboard Partitas.

Some would insist that there are only six keyboard partitas, but as one can be sure there were supposed to be 24 preludes and fugues in each volume of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier, we can be sure that there were meant to be 7 keyboard partitas.

1st in B-flat | 2nd in C | 3rd in A | 4th in D | 5th in G | 6th in E | 7th in F

In music we use the ordinal terms “second,” “third,” “fourth,” etc. to describe the interval between two notes. A note on one scale tone to the one directly above or below it is a “second.” A “third” is one more step, three scale tones starting with the one you are already on.

Here is the sequence of the keyboard Partitas and the intervals between the adjacent ones:

#1 in B-flat, go up a 2nd to

#2 in C, go down a 3rd to

#3 in A, go up a 4th to

#4 in D, go down a 5th to

#5 in G, go up a 6th to

#6 in E, go down a 7th to

#7 in F.

With this series, start with F and go back up skipping one at a time, then down skipping one at at time and you will collect, F G A B-flat C D E. These are the notes of the F major scale, a scale that the final and Seventh Partita completes.

Except, of course, that there is no Seventh Partita. Or I should say, there is no Seventh Partita that we know of. That such a partita was composed seems as certain as Sunday follows Saturday. Have these precious few leaves of music been lost to the brutality of time? Did it get left to an irresponsible heir who sold it to someone who might have tried passing it off as their own? Did a visiting musician make a copy that now survives in a scrapbook or chest of yellowing paper in an attic, or in…?

Those of us who treasure such works have no choice but wait patiently await its miraculous reappearance.

It may seem silly to invest much affection for such a work, something not a thundering piece for a huge orchestra and chorus, something not a huge volume but only a few sheets of paper, but to those of us who are keyboardists as the master himself was hope to find something for us, for only us to understand.

So, we continue looking. We scan the horizons that we can scan. We keep our cyber-eyes peeled for internet detritus of keyboard pieces written in F-Major, auctions of documents from estates…

I am putting these few words up on the internet as a little light that people might see if they happen across a few sheets of music probably beginning with waves of sunny arpeggios tumbling onto a sandy shore on double staves of music in that bright and golden key of F major.

But wait… One more thing. While we are on the subject, there is another matter I’d like to bring up. The Seventh Partita may be a work among those that we know exists that has vanished, but what of works we do not know existed that we know have vanished? How can we be so certain of works that have vanished if we don’t know that they ever existed?

Focusing in on his 5 years in Kothen We know much of Bach’s composing methods from documentation of his former days in Weimar and his subsequent days in Leipzig. Much of the description of his method of composing comes from his son Carl Phillip Emanuel Bach who himself became a composer of such fame as to overshadow his father, at least in his own day. In any case, what a composer would do when composing, say a concerto, would be to compose it on a master score. On the score, he would have a separate stave for each instrumental part. When complete, he would hand over the score to a copyist or one of his sons if they were competent enough, and they would copy out the separate parts. In other words, the violinist’s part would be copied out separately from the cellist’s part so that one could hand each part out to each instrumentalist to perform the work.

So now we have two copies of the work. We have Bach the composer’s copy, which presumably he keeps as part of his personal effects until death puts it in the hands of his estate’s executors, and we have the parts which, in this case, were put into separate folios and put carefully away in the palace library. Bach’s copy traveled and moved house with him. We have cantatas from his subsequent duty at Thomaskirche in Leipzig featuring reworked music from his Kothen scores. When Bach passed in 1750, his scores must have been divided in a way the dividers of such things thought best. If he were a famous composer at that point, the material value of these scores would have helped support his widow and orphans. The palace copy would have stayed in the palace library to await a more distant fate.

We don’t really know what happened to Bach’s composer’s score of these works because we don’t seem to have them. Perhaps they were injudiciously cast into the trash. But what of the palace’s copy? These scores were among the books and special bindings and swirly endpapers of the other books in the royal library. They must exist among the other books in the library of the royal library. Which is completely missing.

Bach biographer Christoff Wolf in his comprehensive biography of Bach, says no more than the library has “simply vanished!” Time can be so brutal to paper, even that hand-made and wonderfully perfect paper of the era. There have been savage wars using the most advanced technology to blow up and burn people and, of course, their papery personal effects. Have these works come to the same fate as the humans who surrounded them in times of war? Have they been exploded or incinerated?

Much of Bach’s work exists to us not in “autograph,” that is, works in his own hand, but as handwritten copies by someone else, or in a very few cases, in published copies. In many cases, a manuscript, maybe a copy of a copy. But as long as we can trace the provenance of the notes to Bach himself, that Bach himself placed each note in its place the way God has placed each star in the heavens, then we have a work of Bach’s music. It’s quite different from the art of paintings, where it’s the actual physical artifact that holds the work’s value. A photo of a Bach work has value as long as the notes are legible and the provenance of the work can be established. A photo of a Picasso might have historical interest, but would be a total loser at a Sotheby’s auction.

By this machinery, original works of art like those of Picasso are subject to competitive bidding until they are so expensive, that they are precious beyond gold or real estate. And in handy trapezoids of flat currency-like commodities. This is important because the bids are placed by the rich and by rich institutions. If a sovereign fund makes the winning bid on a Picasso, they wouldn’t want it somewhere where it might be damaged by light, bad air, weird people, etc. It would most likely be in a vault.

And indeed, much such hyper-valued art must be unknown works by known masters. It has come to light recently of unknown masterworks by Picasso and Cezanne that hang in private galleries of the hyper-rich. By “unknown,” I mean unknown to the public, to most of us. There is no compelling need for those of us who cannot financially participate in this particular commodity market to have any knowledge of the commodities being traded in it. Just as there are “pocket” listings for Kakaako luxury condominiums beyond the reach of most mass-market customers and their Realtors.

But this shady world also reveals some hope for vanished works of music. Bach’s Seventh Partita and certainly the 300 concerti and other chamber works he produced in Kothen would be worthy of bidding by the same financial forces that trade in unknown Picassos.

So let us remain vigilant to these works as though they have made it to our times intact. Let us hope someone reveals their whereabouts. Perhaps someone has taken photos of a score, or a defecting musician from one of the secret ensembles makes a deathbed confession.

Can you imagine the significance of the existence of such a cache of music? To me, it is more reasonable to assume the continuing existence of at least some of these works than to assume that these works have simply vanished! Heads up, people. Keep your eyes open. And don’t be afraid to use your email.

H. Doug Matsuoka (doug@hdougmatsuoka.com)

31 December 2019

Alewa, Honolulu, Occupied Hawaii